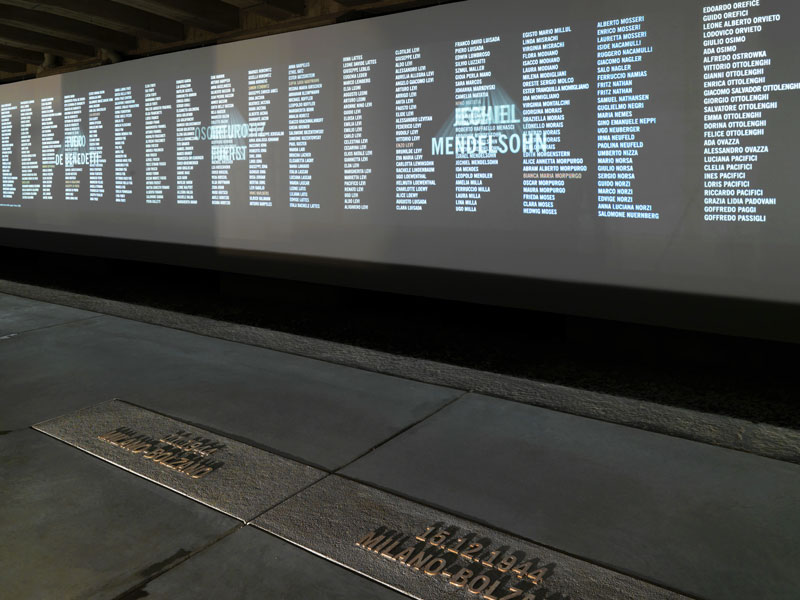

Originally used for loading and handling mail cars, in the years 1943–1945, this place was where thousands of Jews and political opponents were loaded onto livestock cars, which were then lifted to the track level above and joined together into trains headed for Auschwitz–Birkenau, Mauthausen, and other death camps or concentration camps, both abroad and on italian soil. such as the deportation camps at Fossoli and Bolzano.

The first train left on December 6, 1943: out of the 169 people deported that day, only 5 survived the war. On January 30, 1944, the second train loaded with Jewish prisoners left the Central Station bound for Auschwitz–Birkenau. Only 22 of the 605 people deported that day would survive. One of them was Liliana Segre, who was thirteen years old at the time. In spite of her youth, she managed to survive the horrors of Auschwitz; her dearly beloved father did not.

Of all the places in Europe that had been theatres of deportations, the Milan Memorial is the only one that has remained intact. It renders homage to the victims of the Holocaust. It is a vital, dialectical setting where one can actively work through the tragedy of the Shoah. It is a place of commemoration, but also a space for building the future and promoting civil coexistence. The Memorial is meant to be a place of study, research, discussion, and interchange: a memorial for those who were, for those who are, and especially for those who will be.

It is a place symbolizing the deportation of the Jews and other persecuted peoples to concentration or death camps. It is a place for memory and awareness, a multifunctional center for conferences, seminars and exhibitions so that past atrocities will never find refuge in oblivion. Most importantly, it is a venue for dialogue and interchange among cultures, teaching the new generations to overcome linguistic, cultural and social barriers so that the extremes of brutality witnessed in the twentieth century—the Shoah being the absolute nadir of human barbarity—can never happen again.